Eric Degerman; Tri-City Herald

ROSEBURG, ORE.

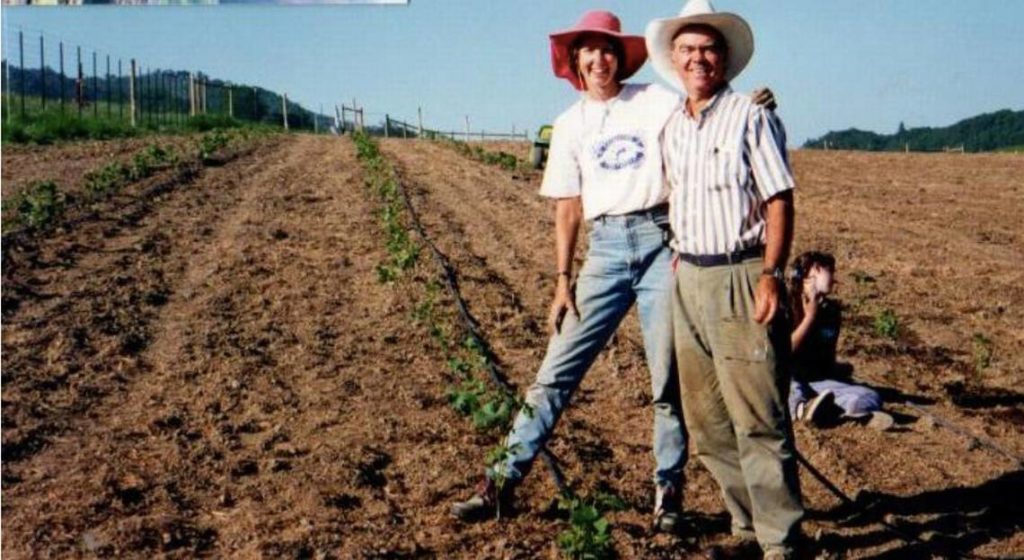

On Memorial Day 1995, Earl and Hilda Jones were living examples of an antiquated Spanish term for planting a grape vine — abacelar.

A quarter of a century later, Abacela Winery near the Southern Oregon city of Roseburg remains a pioneer and icon for the Pacific Northwest wine industry, particularly with Spanish varieties Tempranillo and Albariño. If only Earl’s father, who farmed row crops in Kentucky, were alive to see all that has been accomplished.

“Son, you’ve lost your damn mind,” is the quote that’s become part of the legend surrounding the 76 acres carved out of the 463-acre oak savannah in Umpqua Valley.

His son gave up a decorated career as an immunology researcher to grow grapes and make wine. At the age of 80, Earl chuckles now as he looks back upon the day Fault Line Vineyards was established, which came not long after uprooting his young family from the Gulf Coast.

“You should ask Hilda about that. She can give you a more terse summary,” Earl says with a hearty laugh. “We planted 10,000 vines that spring — 12 acres. The first day, we worked all day and only planted 300 vines. We both couldn’t believe it. Our backs were breaking with the watering. It took us forever to get the 12 acres planted.”

Those were the first commercial Tempranillo vines in the Northwest. Now, there are more than 350 acres of Tempranillo growing in Oregon alone, and more than 50 wineries in that state pour a Tempranillo.

“It used to be, ‘I’ll have a Tempra-NELLO,’ ” Earl says. “And now almost everyone knows it’s Tempra-KNEE-O.”

That’s largely because of the work done by Earl and Hilda, who have become ambassadors in the United States for Tempranillo and Albariño. In 2015, they each were presented with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Oregon Wine Board.

It all began with Earl’s fascination with three regions in Spain – Rioja, Ribera del Duero and Toro. In particular, he points to the Tinto Pesquera by innovative winemaker Alejandro Fernández that led to researching the unique influences of the Duero River.

Armed with data input from his son, Greg Jones, a climate researcher, Earl toured the Pacific Northwest. In time, he ruled out Washington and Idaho because of their occasional harsh winters. He decided upon a parcel not far from the wildlife safari near Winston. The future home of Abacela was secured in 1992, and the variety of soil types found beneath Fault Line Vineyards have fascinated geologists around the globe.

Less than three years later, that memorable Memorial Day planting began at Cox’s Rock, a parcel named for the family that arrived before the Civil War.

It was 13-year-old daughter Hanna’s tasteful artwork of Cobblestone Hill that served as the inaugural labels for most of Abacela’s history and remains the inspiration for the current look. Her talents are apparent to anyone who visits Abacela’s Vine & Wine Center, which Hanna designed and her parents opened in 2011.

Ironically, Abacela’s inaugural commercial wine was a 1996 Cabernet Franc, a mere 36 cases. The headlines stemmed from the 1998 vintage, which produced an Abacela Tempranillo that earned a double gold medal at the 2001 San Francisco International Wine Competition. It also beat out 19 entries from Spain on its way to best of class.

Fault Line Vineyards remains an ongoing research project for Earl, who has experimented with 25 varieties across the family’s estate. The disappointments have been few. Zinfandel was removed after six years. Among the longer trials that have since been transitioned are Cabernet Sauvignon and Cab Franc.

And while most of Abacela is planted on rootstock, the scientist in Jones includes some own-rooted examples of each variety as research. Interestingly, that first Tempranillo — Clone 1 — arrived as budwood from Southern Oregon researcher Porter Lombard. A quarter of a century later, there are six clones of Tempranillo planted across 22 acres. Clone 1 remains the chosen one, albeit rather fickle. Meanwhile, Clone 2 has become the workhorse and the secret sauce for Abacela’s flagship Fiesta Tempranillo.

“I like to pair Tempranillo with something that absorbs the tannins of a young wine,” Earl said. “A lot of foods will do that, but something that has a high-fat content such as meat. Some fish will even work pretty well.”

Five years following the historic Tempranillo planting came Albariño — a variety Abacela again was the first in the Northwest to plant, produce and bottle. These days, Andrew Wenzl, well into his second decade as the Joneses’s winemaker, produces more than 2,000 cases of the brisk white wine from 11 acres.

And when it comes to Wine Press Northwest magazine’s Platinum Judging, a third of Abacela’s 15 career Platinum awards have come with Albariño.

Below are a handful of recent releases from Wenzl and the Jones family that our panels have tasted this winter. Look for them at your favorite grocer or wine merchant, or contact Abacela directly.

Abacela 2018 Estate Albariño, Umpqua Valley, $21: This wildly successful experiment at Abacela began in 2000, and it began with a half-acre on the north side of a hill. Picked at 21 Brix, there’s no oak involved, allowing the grape to exude fanciful aromas of lemon meringue pie, papaya and orange Creamsicle. And yet it is brilliantly bone-dry, making for a delicious, mouth-filling and mouth-watering drink of stone fruit and slate. Enjoy with seafood, paella or a fruit and cheese plate that features quince paste.

Abacela 2015 South Face Block Estate Reserve Syrah, Umpqua Valley, $44: After Tempranillo and Grenache, Syrah is the third-most planted red at Abacela, and some of these vines now are 25 years old. The barrel program of French oak, 28% new, sets the stage with a theme of cherry, milk chocolate and vanilla. It’s far from flabby on the palate as blackcurrant and pomegranate come with plum-skin tannins that combine for a pleasurable and juicy finish.

Abacela 2015 East Hill Block Estate Reserve Malbec, Umpqua Valley, $42: There’s nearly as much of this Bordeaux red planted at Abacela as Syrah, and its roots also stem from 1995. Dense aromas of blackcurrant candy and cherry jam include squid ink and smoke. Inside, it’s a big yet rich wine with huckleberry and plum flavors, backed by boysenberry acidity. As one would expect with the Bordeaux red, Wenzl builds this for the long haul.

Abacela 2015 South East Block Estate Reserve Tempranillo, Umpqua Valley, $49: Aside from the fun and screw-capped Fiesta, the rest of Abacela’s Tempranillo program often doesn’t begin to show its promise until seven years beyond the vintage. The 2015 South East Block is an exception. A deft touch with French oak, just 14% new wood, makes charming levels of baking spice and toast just behind purple fruit tones of plum and black cherry. Its layers of cherry pie and Craisins make for a bright and juicy structure capped by a bit of fresh-baked brownie.

Abacela 2016 Estate Tinta Amarela, Umpqua Valley, $30: This Portuguese variety is a core component to Wenzl’s stellar Port program, yet its success as a red table wine has prompted the Joneses to ramp up Tinta Amarela beyond a wine club offering. Longtime vineyard foreman Darin Cook has no trouble with its ripening, exemplified by the Sept. 16 harvest date. It’s a perfumy, robust yet balanced, bringing a theme of plums on parchment paper, Bing cherry and sweet herbs as bright tannins make for a long finish.

Eric Degerman operates Great Northwest Wine, an award-winning media company. Learn more about wine at greatnorthwestwine.com